Images: Mary Jo Porter

If paradise ends where choice begins, as Arthur Miller observed, then our digital age fantasy of paradise as a tropical island with no Internet collapses with our choice to travel to one. The permanent inhabitants of such an island, who live without Internet access or the luxury of travel, would likely have a lot to tell the world about life in paradise, if only they could get online. As of 2016, these inhabitants represent 95% of the Cuban population.

In January of 2008, Seattle resident and transportation engineer Mary Jo Porter set off on a trip to Cuba lugging a raised toilet seat and other supplies for the friend of a friend on the island. She knew she wouldn’t be landing in paradise. Anything else she knew about daily life in Cuba she had gleaned from a friend’s daughter who worked there and a lone blog she had found online called Generation Y.

When Porter visited Cuba, the author of Generation Y, Yoani Sanchez, was on the verge of international renown as a leading human rights advocate and intellectual. Sanchez started her site in 2007, becoming one of the first Cubans to blog about daily life on the island—an endeavor that was complicated by the fact that she, along with most Cubans, was prohibited from going online.

While Sanchez is now considered the pioneer of the Cuban dissident blogger movement, Porter is the reason that Sanchez and bloggers like her have enjoyed such an extensive readership among non-Spanish speakers. For what Porter could not have known when she went to Cuba was that, within months of her return to the US, she would be Sanchez’s unlikely translator. Soon after that, she would become an essential link in an underground network of activists who support Cuban bloggers, and the co-founder and organizer of a website called Hemos Oido [We’ve Heard (You)], the first open and automated platform of its kind where volunteers can go to translate the blogs of Cuban dissidents.

The exchange that follows took place by phone and email during the winter of 2016.

Hillary Gulley (HG): You first came across Yoani’s blog, Generation Y, while preparing to take a trip to Cuba with a friend. What was it about your experience on the island that compelled you to keep reading her blog after your vacation was over?

Mary Jo Porter (MJP): Cuba grabbed me. I don’t know how else to say it. I’ve traveled to quite a few places and lived abroad, but only in Ireland did I have a feeling similar to when I arrived in Cuba: that of being home. The Cuban landscape was immediately familiar, similar to California where I grew up and, like in Ireland, the people were deeply familiar despite the language barrier. Cubans are like Californians: outgoing, casual, willing to tell you their life story on a street corner, and everyone has an opinion about everything. Cuba hadn’t settled in my consciousness since the Cuban Missile Crisis, but once I went, I was hooked.

HG: When you visited Cuba you knew very little Spanish. How did you overcome the language barrier?

MJP: Face-to-face you can probably communicate with anyone if you try. In Cuba, I was often with my friend’s daughter, Jenny, who was working for an NGO there; she interpreted for me on many occasions. Other times, I’d talk to Cubans who had some or a lot of English.

Image: Mary Jo Porter

HG: Did Cubans seek you out for conversation, or did you approach them?

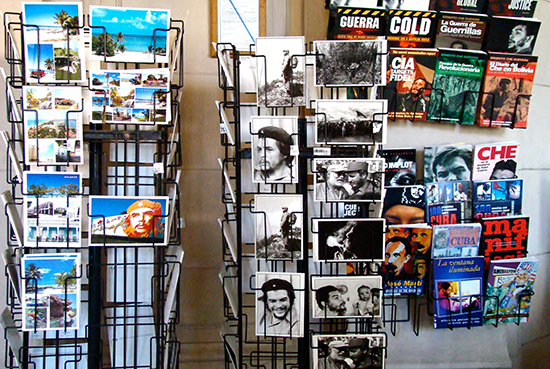

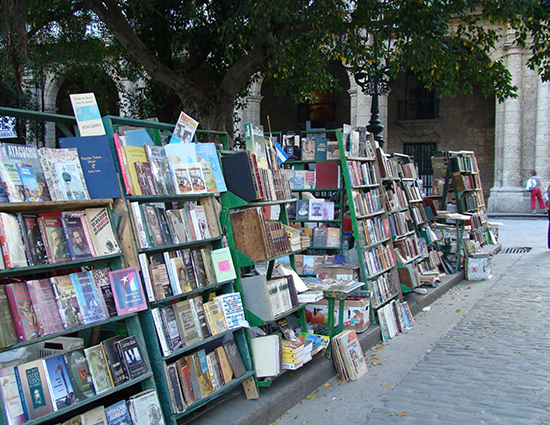

MJP: Both. I had a great conversation with a bookseller at a market in Plaza de Armas. He asked if I was Canadian, and I said no, American. And he said, in perfect English, “I have some excellent books about Che.” When I told him I had no desire to read about a psychopathic, totalitarian murderer, I thought he was going to fall over. Really, he almost stopped breathing. Then he couldn’t stop laughing. When he got serious again, he told me I was “different from other Americans” who came to Cuba, and then spent a good part of the afternoon filling me in on Cuban history, like the time Castro ordered Camilo Cienfuegos (his former head of armed forces) to fly to Havana from Camaguey, and his plane “crashed into the sea.” Except they never found the plane—and the route from Camaguey to Havana is over land. I learned a lot that afternoon.

One day I talked to a butcher at a ration store who didn’t have any meat or chicken or fish. He was reading the paper with nothing to sell, so he had plenty of time to talk. Another time I walked into a tiny barbershop and talked to the barbers and customers. And well after dark one night, my friends and I talked to people playing dominos at a card table right in the street. They had put the table under a streetlight and pointed out that it was the only light working in the area.

Then we went to Viñales and stayed in a casa particular—a Cuban B&B. We had a lot of time to sit around and work through the language barriers. The owners had some English and a lot to say about trying to run a private business and coming up against the Committees for the Defense of the Revolution. I went out to fly kites I had made for the local kids, and one of their dads came out and started fixing them to make them better. So that was another way to connect, by playing.

Another conversation was with a cop guarding the American Interests Section. My friends and I were walking along the Malecón late one night and saw a huge billboard equating Bush and this unknown (to us) “evil person” to Hitler. I wanted to know who the guy was, so I crossed the street to ask the cop. He frantically motioned that I wasn’t allowed on his sidewalk, and he couldn’t cross over to mine, so we met at the center line. It seemed odd to stand in the middle of an arterial in the dark, but it worked fine, because there were no cars—because they’re just weren’t any. He didn’t understand English, and I could hardly make myself understood in my bad Spanish; but I did understand when he called someone on his walkie-talkie to ask permission to tell me the “evil guy’s” name. He had to call three or four people, moving up the line, before he got someone “high up enough” to give him permission to tell me. Then I couldn’t understand what he was saying, so he wrote it for me on a scrap of paper.

HG: Who was the third evil person?

MJP: Luis Posada Carriles, someone who ultimately has been classified as a terrorist by both the US and Cuba.

Images: Mary Jo Porter. Images: Mary Jo Porter. Along the Malécon as it passes the American Interest Section. These kinds of anti-US government billboards are not common, although images of the five men imprisoned in the US as Cuban spies are everywhere. The man who, with Bush, equals Hitler, is Luis Pasado Carriles. Born in Cuba, he is an anti-Castro terrorist charged in Panama with trying to kill Castro, and in the US and elsewhere with other crimes. Bush approved his release from prison in April 2007, against the advice of the Justice Department. The New York Times headline read: “A Terrorist Goes Free.”

HG: You also took portraits of some of the people you spoke to.

MJP: You can usually buy postcards of the sights wherever you go, so I tend to focus on “urban-y” and transportation things—bike racks and intersection configurations—and people. But in Cuba there were only postcards of Che, and no mail service to the US, so there was no point anyway. I like portraits, and if you want to get one, the person generally has to cooperate, so, voilà, a great way to get talking to people.

Image: Mary Jo Porter

HG: Do you think Yoani’s blog captivated you because it brought you back to the daily lives of the people you met while you were in Cuba?

MJP: Of course Yoani’s voice, and especially then, so intimately placed in the minutiae of her life and the lives of other Cubans on the island, was captivating. But it might be overstating it a little to say that was the major reason I became so engaged in it, because you have to remember, there were almost no blogs coming out of Cuba, from the island itself, at that time. Yoani was pretty much it. Of course if her blog had been a lot of disengaged ranting, I probably wouldn’t have continued to read it. So yes, it was that intimate focus that really drew me in, but I was looking hard, online, for something, anything, to read that was written on the island.

HG: You say her writing focused on everyday life “especially then”—what changed?

MJP: A few years ago, a journalist asked me if I thought Yoani’s blog had moved away from that immersion in daily life. This was after she started traveling. I said she still chronicled her daily life, but that it had changed so drastically: if she just wrote about how bad the coffee is, and how her coffee pot exploded along with everyone else’s when the government put too many crushed peas in the coffee, it wouldn’t feel authentic anymore. Great, her coffee pot exploded (or didn’t), but the New York Times said she met with Jimmy Carter in Havana yesterday—why isn’t she telling us about that?

HG: Did you notice any connection between Yoani’s blog and the narrative that emerged from your photographs back in 2008?

MJP: Clearly everything about me and my worldview and my way of seeing, thinking, feeling, writing, are my own and not Yoani’s. But I felt a connection to the point that I wanted to try to share her voice with other English speakers.

But you’ve made me realize there is kind of an odd dissonance here, because while my voice is not Yoani’s voice and vice versa, Yoani’s voice in English is my interpretation of her voice, which cannot help but get overlaid with my own voice and the words I choose and the way I phrase things. So inevitably there is a distortion of her in what I do. That is translation. It’s unavoidable.

HG: Can you talk a little about this “distortion” in translating Yoani and other Cubans?

MJP: I will say I have tried hard not to intrude, which leads to a whole other conversation about translation and the choices of words and phrasing that I made early on when I didn’t know the language, choices I almost certainly wouldn’t have made had I understood, in a native kind of way, what she was saying.

But I think these same choices accidentally set a pattern that was powerful for many reasons. Cubans for whom Spanish is not their “everyday” language—even if it is their first language—have been the most enthusiastic about my translations, while naturally it seems they would be the least happy, because they bring the best language skills to it. But then I realized it isn’t because the translations are so “good” in the traditional sense—because they’re not—but because, for fear of getting it wrong, I left so much of the “castellano cubano” in the English text. And that was a conscious decision: not to please Cubans in exile, but to try to bring “more” of Yoani and more of Cuba and Cuban Spanish to the English-language reader.

HG: Do you think your approach to translating Yoani’s blog may have attracted a larger readership in English? One that began with Cubans in exile who recognized, in your translations, strains of a Spanish they were familiar with but did not use every day?

MJP: No, not at all. Yoani’s blog would have attracted a huge readership in English with any reasonable translations. I think Cubans in exile, and more to the point, the children and grandchildren of exiles, enjoy seeing the words of their parents and grandparents reflected in the word choices in the translations, but not to the extent that it generates more readers.

I have seen other translations of Yoani’s writings here and there, and with one exception, they have all been excellent.

HG: How did the exception go wrong?

MJP: There was a photo book being prepared on the architecture of the “Cuban New School”—i.e. Socialist Brutalism. They asked Yoani to write a short piece to accompany some photos of a boarding school in the countryside that had been part of the “schools in the countryside” project that her generation had attended. Yoani’s response was a dark essay titled “Concrete Forms to Forge a ‘New Man.’” It opened with the story of a fellow student who committed suicide by jumping off the roof of the school.

The translator made Yoani sound like a Valley Girl. It was hilarious, but horribly so. The editor asked for my help, and I retranslated it. I did wonder what kind of impact Valley Girl-Yoani might have had if she’d been translated that way from the start.

HG: You started translating Yoani’s work shortly after you got back from Cuba in 2008: Yoani’s previous volunteer English translator stopped, leading her to post a help-wanted ad on her blog. You answered after a few weeks went by and no one else did. Is that right?

MJP: It was a few weeks at most, and it wasn’t really a “help-wanted ad,” it was a little “by the way” at the bottom of a post. A sentence or two. Other people did answer, but I guess she got my “translations” first.

HG: Can you describe the process of confronting Yoani’s writing as a novice translator who didn’t know much of the language you were translating from? What was your approach?

MJP: To say I was a “novice translator” at that point is a huge overstatement. My approach was to ask for help translating by using my computer skills and—most importantly—those of my partner-in-crime, Karen Heffner Chun. Karen and I met when we were eight, and we’ve been friends longer than we imagined we’d even be alive. She’s been with me since that first day when Yoani sent me the password to the English site and said “it’s yours now.”

Along with the password, Yoani sent me “instructions” about how to use WordPress, which wasn’t as common then as it is now. The background of the site was all in German, because it had been set up by her friend in Germany, and at the time there was no “change language” function. Her accompanying instructions were in Spanish. Fortunately, little things like foreign languages don’t stop Karen, and we got it working.

That first night, we posted a “help” request in the domain’s sidebar; by morning a posse of volunteer helpers had arrived. There was also another woman who had offered to help, Susanna Groves; Yoani gave me her email, so she and I started off together. She quit later that year to help get Obama elected, but by then there were already a lot of people who had stepped up to help translate.

HG: As the demand for translators grew along with the Cuban blogosphere, you and Karen founded an automated site called Hemos Oido, where volunteers can access and translate Cuban blogs into English, French, German, and Dutch; then you founded another site for English readers called Translating Cuba. Can you talk about the process of founding the sites and how they work?

MJP: By the time Karen and I created Hemos Oido, we were already translating more than twenty blogs. But it was all case-by-case, with people responding to the request for help on the sidebar; then I’d manually send them links to blog posts. So as Cubans on the island were writing more, and more people were offering to translate, it was getting unworkable.

Karen suggested we try to put the translating online. We started using Google Docs, which was labor-intensive in terms of manually loading posts so multiple people could work on them; we did it for a few days and were overwhelmed by the response.

So then Karen designed and coded Hemos Oido, a platform that automatically picks up new posts from any blog we link to. Volunteers can then access the posts on the site and translate them there. The site notifies us when the posts have been translated and automatically publishes the translations. Then, to make those translations more accessible to readers, we created Translating Cuba, a site that automatically pulls in all of the blogs that have been translated into English so they can be read in one place.

HG: And Hemos Oido is an active site where volunteer translators can go to help dissident bloggers.

MJP: It is—and it’s growing. It worked great for several years, but now it’s breaking down again. The problem we’re having is the result of great things happening on the island—and I’m not referring to the “thaw” or the regime’s extremely limited reforms.

It’s that the number of voices is exploding, along with the variety of places people express themselves. So we can’t just go look for good blogs and link them in anymore. Also, many of “our” bloggers are posting the same content on multiple sites. That’s a great thing, but Hemos Oido as a program can’t search out this content, make judgments about what should be translated, and pick it all up; that requires humans. We also need to make sure that the same text doesn’t load to our site more than once from different sources, and that volunteers don’t waste their time translating something that’s already done before we catch the overlap.

HG: Do you have any solutions on the horizon to keep up with the expansion?

MJP: We haven’t figured out exactly what to do. We do have “off-line” helpers, people I’ve gone back to assigning posts to. Alas, a couple of our best translators are anonymous, and I have no idea who they are or how to ask them if they want to help in this way.

Karen and I are still stuck with working for a living—and to support the project—so we don’t have infinite free time to do everything we would like to do. It’s already a full-time job for me, but it needs to be more than that.

The same problem applies to people from other countries who want to do something similar to what we’re doing with Cuba. We’re eager to help them set it up, but again, no one has been able to pull it off yet. The reality is, everyone has to work for a living, and when they realize how much time this involves, they just can’t commit.

Image: Mary Jo Porter

HG: Do you think any of the skills you use in your day job as a transportation engineer transferred to your work as a translator and founder of Hemos Oido and Translating Cuba?

MJP: I joke about this, but yes, in a very odd way. A lot of the work I’ve done in transportation is translating. I was deputy director on Seattle’s light rail project, and a lot of what I did was “translating” all the engineering speak for elected officials and the general public, and in some cases translating in the other direction as well.

I would say, however, that translating engineering speak to plain English is really straightforward. On Hemos Oido, I started out translating a language I didn’t know, which is not only not straightforward, it’s impossible. So the volunteers have played an essential role in teaching me the language and the cultural and historical context; without them there would be no project. I value and thank them more than I can possibly say.

HG: How did the initial support system of volunteers continue to grow around you after you posted the help request in the sidebar? To what extent do you know and have contact with each other?

MJP: The first Cubans who contacted me in 2008 in response to the sidebar request eventually drifted away; I’ve never met any of them.

After that it just grew. In early 2009 I got in contact with Ernesto Hernandez Busto, a Cuban living in Spain who was running Penultimos Dias, one of the most important news sites about Cuba. The site now has a more limited focus on the arts, but it remains active. He is also a translator and he started helping me—and by “helping,” I mean he and I have exchanged over 900 messages. We ultimately met in New York and remain in contact.

Norma Whiting emailed me in 2009 or earlier (2000+ messages to date) and started helping on everything. Eventually she became Miriam Celaya’s translator, and we became great friends. She is a cousin, by the way, of Adolfo Sainz, one of the prisoners of the Black Spring.

Also in 2009, I got an email from Raul Garcia Jr., a young Cuban American living in Miami. He wrote (in Spanish) “for some time I’ve wanted to help the blogger movement in Cuba. The problem is I don’t know how.” From that first email he basically devoted his life to helping people on the island. His own motivation was a desire to support and honor his father, who had been imprisoned in Cuba at age 17 for joining the movement against the Revolution. In addition to another million things, Raul became a key member of the support network abroad for the political prisoners from Cuba’s Black Spring, who were driving the regime crazy blogging “Behind the Bars.” He also helped them when they were finally released; most of them were forced into exile.

Isbel Alba, a Cuban exile who I eventually met in Quebec, contacted me maybe in 2010 or possibly earlier. She also had a very influential website about human rights in Cuba, and she introduced me to Alexis Romay, a Cuban novelist, poet, musician, and teacher living in New Jersey, and Ernesto Ariel Suarez, a Cuban writer and translator living in Kansas City. Those two can tell me the entire cultural background of all things Cuba starting with Columbus’s landing and continuing up to last week—not to mention explain how Cuban Spanish works in ways that I finally “get it.”

And most critically, a couple in Canada—a Cuban and a Chilean—who posted Yoani’s blog posts for her for years when she couldn’t even see her own blog from the island. They have been my most important help of every kind: learning the language, managing the blog, expanding to lots of blogs. They pretty much fly under the radar, so I won’t mention their names, but we basically just connected through chat programs and stayed in touch all day, every day for a few years.

A non-Cuban I can’t fail to mention is Ted Henken, a professor at Baruch College. There is a series of something like ten or fourteen three-minute videos he made of an interview with Yoani, back when you could only record and post videos of that length on YouTube. He has supported Translating Cuba and me personally in every possible way.

The “posse” eventually grew to include Cubans on the island who spoke English and managed to finagle reasonable Internet access. The most important of these is Orlando Luis Pardo Lazo. I first needed his help translating his own work, because he makes up words and mixes languages and puns. So we were close before I met him in NYC on the same day I met Yoani. He invited me to participate in a photo contest for Cubans on the island, and to submit an article to a digital magazine he was publishing, Voces (Voices). And now, though he’s living in exile in Iceland, I still translate for him and he for me.

HG: Internet access was largely off-limits to Cubans until last summer. Now, the public Internet lounges that have popped up around Havana charge $4.50/hour, or about one-fifth of a Cuban’s monthly wages. Those lucky enough to own a device can buy Wi-Fi access for $2/hour at the new public hotspots. How has the enhancement of telecommunications in Cuba affected the bloggers and your work with them?

MJP: It hasn’t had that great of an effect yet. It’s a little easier for me to communicate with people in Cuba, because they are more likely to see my emails in less than a week and more able to respond. Previously, that might have taken a few weeks. But still, service is so bad and so expensive that it’s nothing like having broadband at home.

There continue to be a lot of ways Cubans get access to the Internet. Several embassies offer Internet access to Cubans; I know a few bloggers who have a weekly time slot at an embassy to get online for an hour. Also, because home internet there is dial-up (though they’re supposedly starting an experiment in home broadband in Central Havana), people who do have it—almost entirely people on the government’s good side—can “sell” their dial-up phone number with their log-in and password by the hour. So you might buy 3 a.m. to 4 a.m., and you agree to log on at 3:01 a.m. and log off at 3:59 a.m., and not one second later, because someone else has bought 4 a.m. to 5 a.m.; and you agree not to go to “bad” websites, like politics or porn, that would get the account holder in trouble. Others might have access only at work, but they can send and receive emails for themselves and for friends, or for people who pay them.

It’s important for people to understand that the bloggers—at least in the earlier years—didn’t just sit in their homes or embassies or hotels and blog. They relied on a network of volunteers from all over the world—very informal, set up by Cuban-to-Cuban contacts—who would create and manage the actual blogs, hosted abroad, and they would post by email through these intermediaries. The bloggers didn’t see their own blogs. And I know this way of working continues for many today. It’s more reliable, and cheaper. And there are a couple of million Cubans outside of Cuba (and more every day), so it’s not that hard to find someone willing to help you.

HG: Were you ever afraid to trust any of the help you received, translation-related or otherwise, given the political stakes inherent to the writing of these bloggers?

MJP: It never occurred to me to distrust advice on political grounds, my own naïveté showing I guess. Speaking of Yoani’s writing in particular, it would have been hard to distort it politically. For example, she’d write articles like, “I live on a tropical island. I have a cold. Why are there no lemons here?” When she wrote about days of “incredible swaps” to get suture thread so that her friend’s mother could have surgery, and having to bring sheets, food, and cleaning supplies to the hospital, it tells us more than all the rants and statistics ever could about the current state of Cuba’s highly vaunted healthcare system. It was that approach, and her lack of political rants, that made her such a powerful voice from the beginning.

I was led astray more than once, however, by translations in good English that I assumed were perfect that were far from it, but not for nefarious reasons—simply because I assumed the volunteers spoke Spanish and it turned out some of them, not so much.

But the worst mistakes have been my own, and there were some doozies. One of my “favorites” was a post where the first word was “Leo.” I couldn’t figure out the grammar of how this Leo guy fit into the sentence, but I made it work; he appeared two or three more times in the text. It was maybe the Dutch translator who asked, “Who the hell is Leo?” It turns out “Leo” means “I read”; it wasn’t a man’s name. Another time the Dutch translator saved me from translating “umbrella” as “wool socks”; I do remember thinking, Who in Cuba owns wool socks?

HG: It’s possible to imagine what demographics might be reading the blogs in Spanish, if it isn’t Cubans on the island, but who is reading the translations?

MJP: I wish I knew precisely. We have a stats program that gives us the usual information: how many readers, where they come from geographically, what they search on, what posts they read the most. But it doesn’t really tell us who they are.

Encouraging, however, is how many quotes and links we’re getting to our articles from the mainstream press. I’ll read articles in the New York Times, the Washington Post, and Foreign Policy and see “our” words—which means the voices of Cubans on the island—in these sources of influence.

HG: How has normalization affected the Cuban blogosphere? Has it increased the number or reach of bloggers within Cuba?

MJP: “Normalization” is very young, and certainly in Cuba the physical attacks on and arrests of human rights activists seem to have intensified. I don’t think we’ve seen changes in freedom of expression and the press. Opposition blogs, websites, and Yoani’s digital paper are still censored on the island. Miriam Celaya wrote a great article on the subject.

Probably the most significant “transition point” from there being just a couple bloggers to lots of bloggers was the Blogger Academy project, which is when Yoani and her colleagues started offering workshops to aspiring bloggers on how to use social media tools and WordPress.

And of course when the government dropped the exit permit requirement, and Yoani and other human rights activists on the island started traveling the world, everything changed enormously.

Image: Mary Jo Porter

HG: As early as 2008, Yoani had been named one of Time magazine’s “100 Most Influential People in the World” and listed among Foreign Policy magazine’s “Ten Most Influential Latin American Intellectuals.” But because the Cuban government didn’t drop their exit permit requirement until 2012, Yoani wasn’t able to leave the island until 2013. You accompanied her on her first trip to the US that year. What was your experience? Was it the first time you met her?

MJP: It was March 2013, and yes, it was the first time we met after five years of working together. Before that I’d had one or two brief calls with her, but with a price of US$ 1.00 per minute to call Cuba, I couldn’t afford it; and with my lack of Spanish and her lack of English, there wasn’t much point in our trying to talk on the phone. Also, the few times I did call, we kept getting cut off. State security? Bad phone service? I have no idea.

So what can I say? Meeting her in person, getting to hug her, was fantastic. Who she is didn’t surprise me, but it made me very happy, because she is the person I thought she was, only happier, more cheerful, and funnier. At the end of grueling days of being on, with events and interviews nonstop, she never flagged or lost her sense of humor. We shared a hotel room, so we were together 24/7; and when she finally had quiet time, she was still smiling and laughing.

There were many high points, but one that really sticks out for me was her press conference at the United Nations. Basically, the Cuban government went nuts about the idea of Yoani being allowed to step foot in the building or use any of the official facilities for a press conference. They wrote a formal complaint, saying it would be an “anti-Cuban action” and “grave attack” on the spirit of the United Nations. So she wasn’t allowed to use the “official” press conference room. But she’d been invited by the UN Correspondents Association, which has its own little space in some far corner of the building; they said no one could tell them what to do in their own space. But the only place they had that was “big enough” to set up in was a wide spot in the hallway next to the copy machine; some of the reporters had chairs, many were standing, and some were sitting on the floor. And Yoani was just so articulate, so elegant, in making the case for the basic human rights of the Cuban people.

HG: A protest erupted during one of Yoani’s US appearances and you were there. People shouted and unveiled signs in support of Castro and against Yoani, which caused another group within the auditorium to start chanting Yoani’s name in support of her. Why do you think Yoani’s writing poses such a threat?

MJP: In New York City, there was an incident with some old white people (like me) who (unlike me) never got over how “fun” it was to protest for civil rights and against the Vietnam War, and who want to reprise that “success.” They totally ignore that despite some significant gains on all fronts, we now have Black Lives Matter, making it clear we haven’t come nearly far enough on civil rights, active troops still in Afghanistan, our longest involvement in any war ever, and a minimum wage that isn’t enough to live on. In the United States, these are perhaps the most important causes of our time, along with global warming.

These old white people, apparently unwilling to take responsibility for how much we have all failed to achieve in our own country, like to believe there’s some fairy tale paradise ninety miles offshore, and that the rest of us are all too deluded—by CIA propaganda? I don’t know, I really don’t know what these people believe—to admit it.

So for the people who didn’t manage to create their own paradise, Yoani is killing a lifetime of dreams that there really is a better world someplace, right here on earth, rooted in freedom and equality, brotherly and sisterly love, kindness and human understanding. As for the threat to the Cuban so-called communists, aka the power elite, I won’t pretend to speak for them. But it’s not hard to imagine their thoughts.

HG: Protesters also accused Yoani of being translated by the CIA.

MJP: The one time I was in the room when people accused Yoani of being translated by the CIA, she looked at me rather amused and asked me to take the microphone. The old white people screaming away did shut up when they saw this other old white person saying, “It’s me, I’m ‘the CIA,’ and is my check lost in the mail or what?!”

HG: Do you think Yoani is used to the protests yet?

MJP: One large event I attended was nearly shut down by the pro-paradise versus it’s-not-paradise-it’s-a-totalitarian-hell crowds shouting at each other. Yoani couldn’t have gotten a word in if she’d wanted to. Basically she watches this stuff in a sort of delighted amazement at what happens in a free society where people are allowed to express themselves.

HG: Have you gone back to Cuba since your initial trip there in 2008?

MJP: Alas, no, and I really want to. I was planning to go a few years ago, but was advised by some foreign journalists stationed there not to do it for my own safety. But I think now, with the thaw, I probably could, and I’m hoping to find a way to do that.

Image: Mary Jo Porter

HG: Has your work with Yoani changed the way you reflect on that first trip?

MJP: Only slightly. The introduction I got to the country through Jenny and the Cubans I talked to was totally consistent with what I read in Yoani’s blog then and later. Clearly a future trip would be very different, and I really want to go back to meet all the people there who are now my friends. I desperately want to hug them and share a laugh . . . about anything . . . my horrible Spanish . . . anything.

But certainly my work with all the Cubans we translate has changed the way I reflect on the whole world, past, present, and future. I see things through a different lens—a clearer lens, I hope—and I’m more tolerant of people I strongly disagree with, much less judgmental. I can now understand how a totalitarian state can sustain itself over so many decades and I find it completely inexplicable at the same time. So I’ve learned to hold completely contradictory viewpoints in my mind. Maybe I’m becoming a little Cuban!

HG: Has your relationship with language changed over the years since you started your work with the Cuban bloggers?

MJP: Oh, of course. I still have problems with the small things—did the man bite the dog or did the dog bite the man—but I now have a whole new language, a culture, a history, a present, hopefully a future. It makes me wish I spoke every language in the world, living and dead. I wish I could talk to anyone anywhere, and I wish I not only had the words, but the whole cultural understanding to really communicate.

I was telling a friend I hadn’t seen for decades about translating Cubans, and she nailed it: “You always were obsessed with words,” she said. The words are great fun, but context is even more so. It’s all been a gift to me in a way I can’t even describe. I guess it’s obvious, because I’m now embarking on my ninth year of this. I’m not motivated by a bleeding heart, but more by a happy, engaged heart, always excited by new voices and new perspectives—though that’s not to say I don’t sometimes get depressed to the point of tears by it all.

HG: You are reluctant to say you were a novice translator when you embarked on this adventure. Would you call yourself a seasoned translator by now?

MJP: Alas, absolutely not! Again, it’s the simple stuff that still trips me up, and it really, really bothers me that I have such a hard time fluently understanding spoken Spanish and speaking it. My increasingly deaf ears (too many rock concerts in the sixties, literally) are always playing catch-up in English, and so much more so in Spanish.

But there are moments, more moments than not now, when I’m translating and I just feel like I’m flying. There’s a certain writing style we like to call “Cuban baroque,” which is basically making the structure of every thought and sentence as complicated and arcane as possible. That can be trying. But there are others who write with a fluidity and clarity and whose thinking is so interesting, and who can frame an idea and phrase it in way that it carries you along; you can feel your brain cells lighting up. And I will say, when I feel I’m getting that right—well, it is a very deep pleasure.

© Hillary Gulley. By arrangement with the author. All rights reserved.