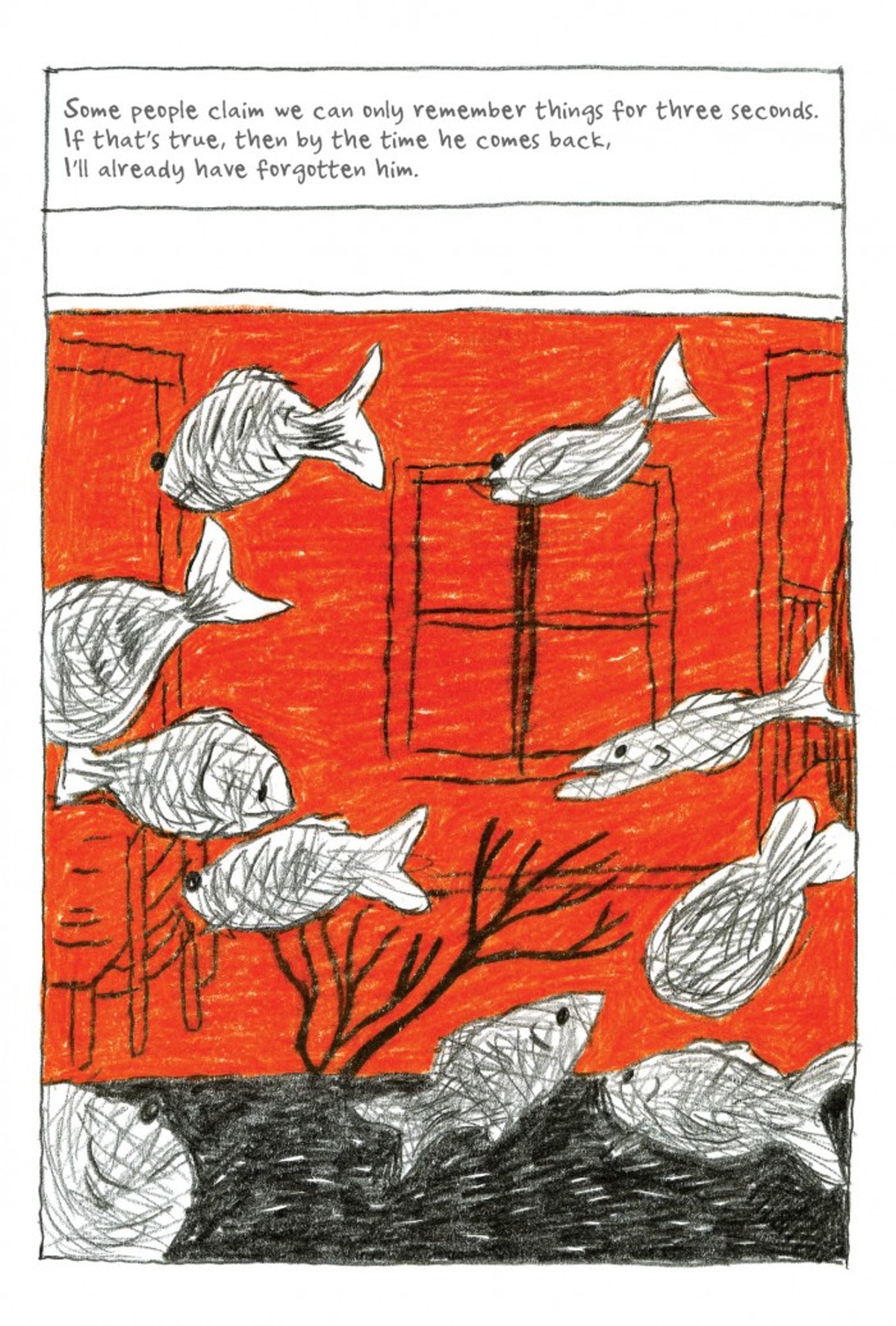

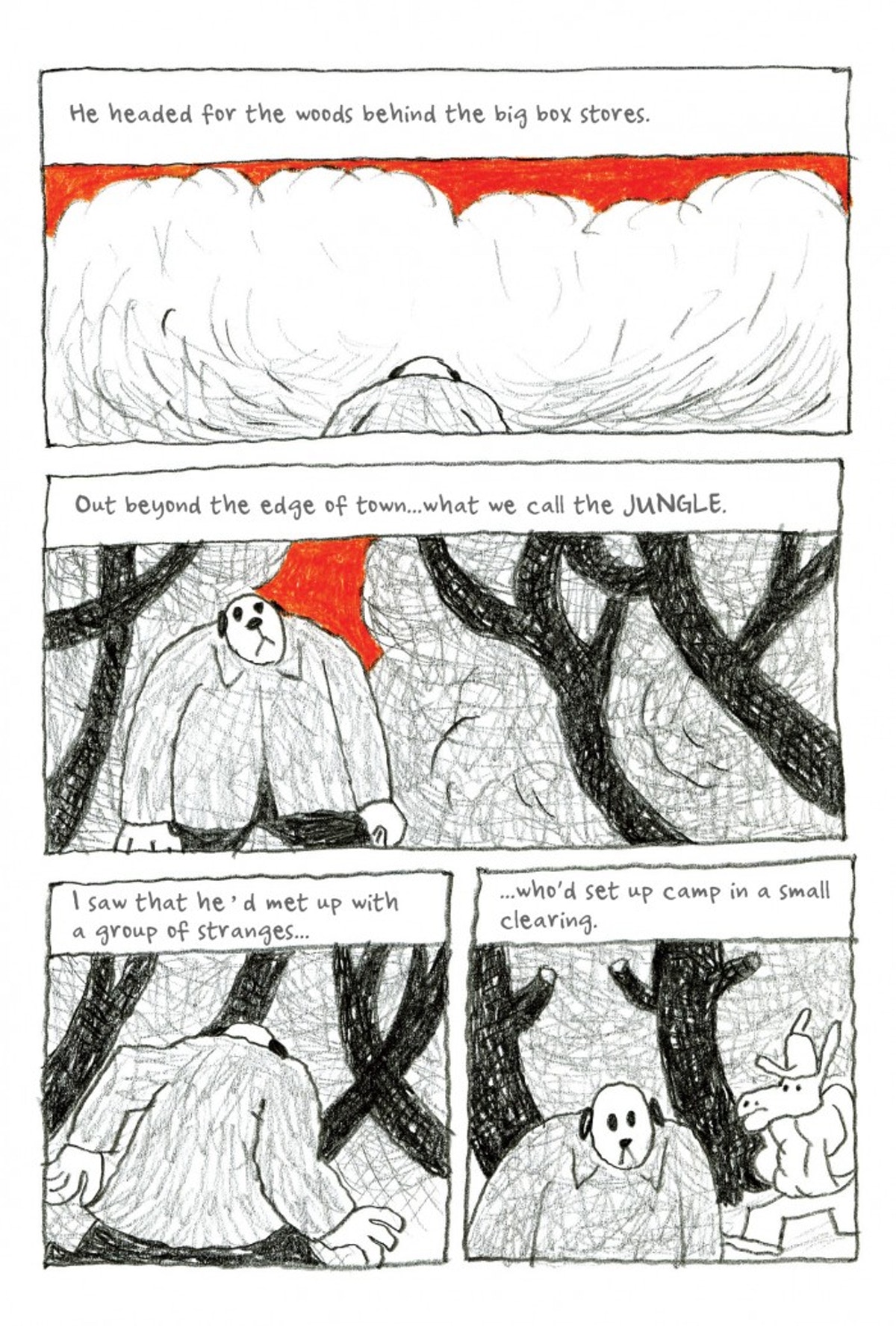

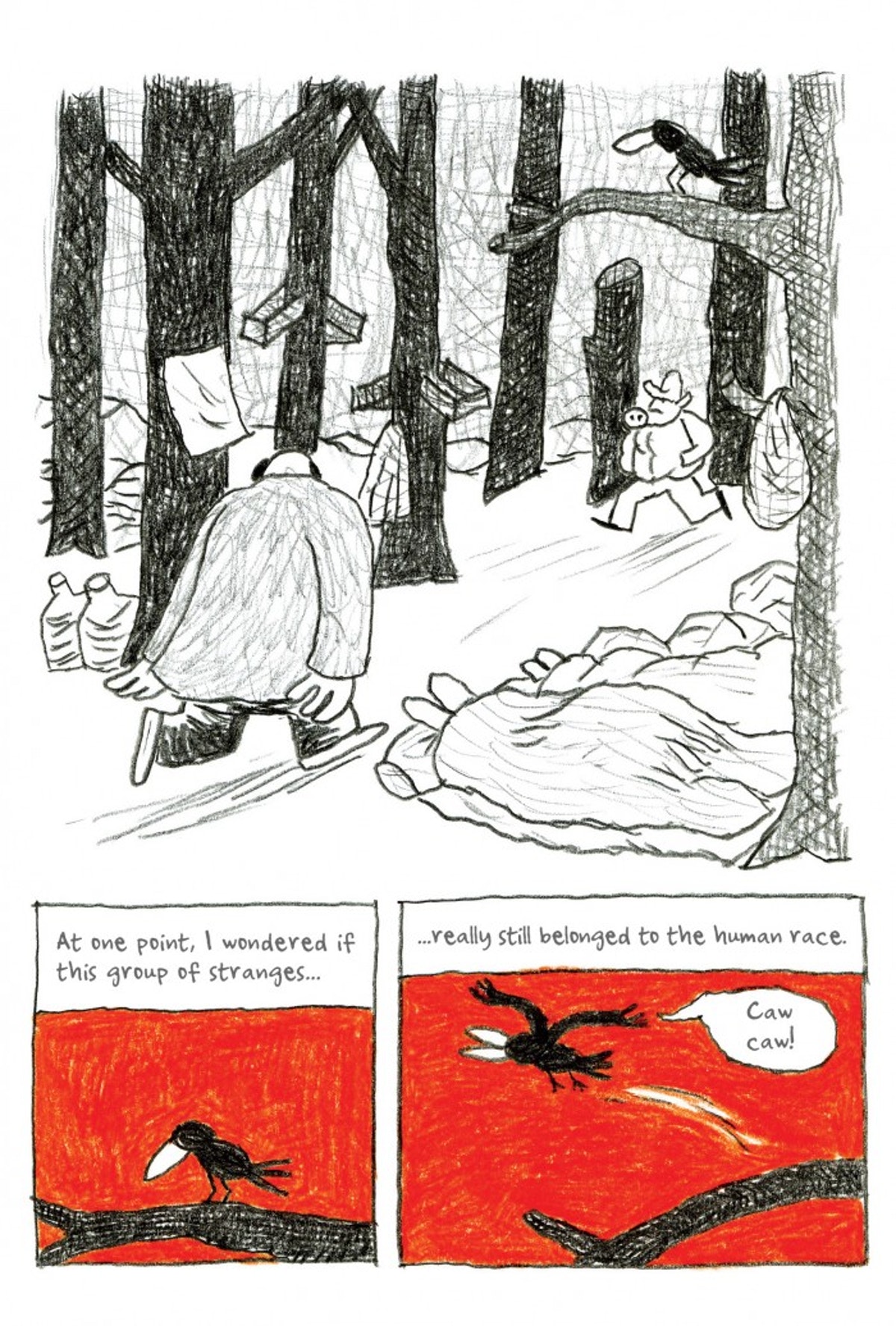

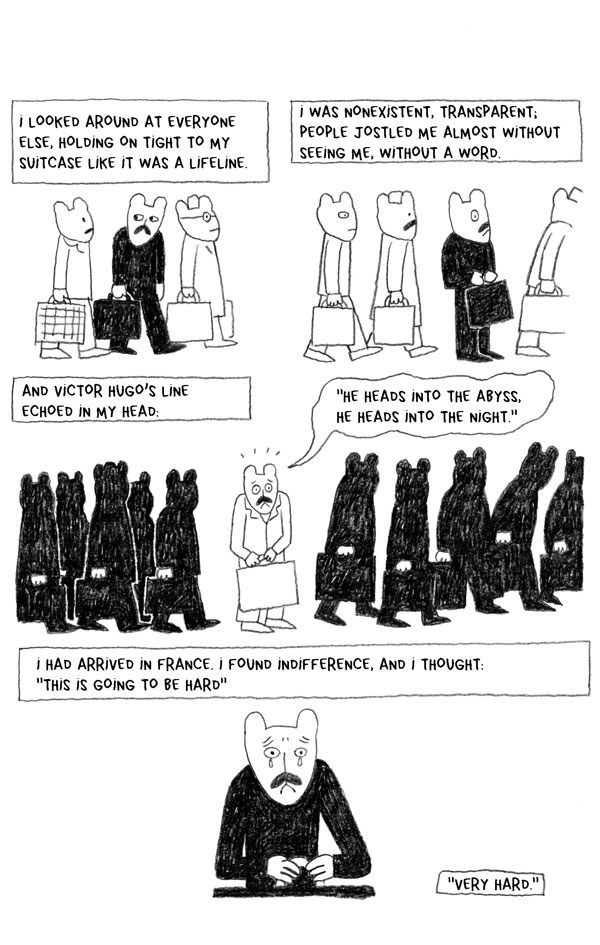

The relevance of Jérôme Ruillier’s delicate allegory to the current refugee crisis requires little preface, but the title and conceit of his book bear closer examination. In hopes of a better life for his family, Ruillier’s unnamed protagonist undertakes a perilous, costly, and yes, illegal migration. Like him, his troubled homeland and the developed nation where he ends up are anonymized. The title, L’Étrange, becomes the label slapped on Ruillier’s protagonist: a word that typifies rather than specifies, a word that wards off at arm’s length, averse to understanding.

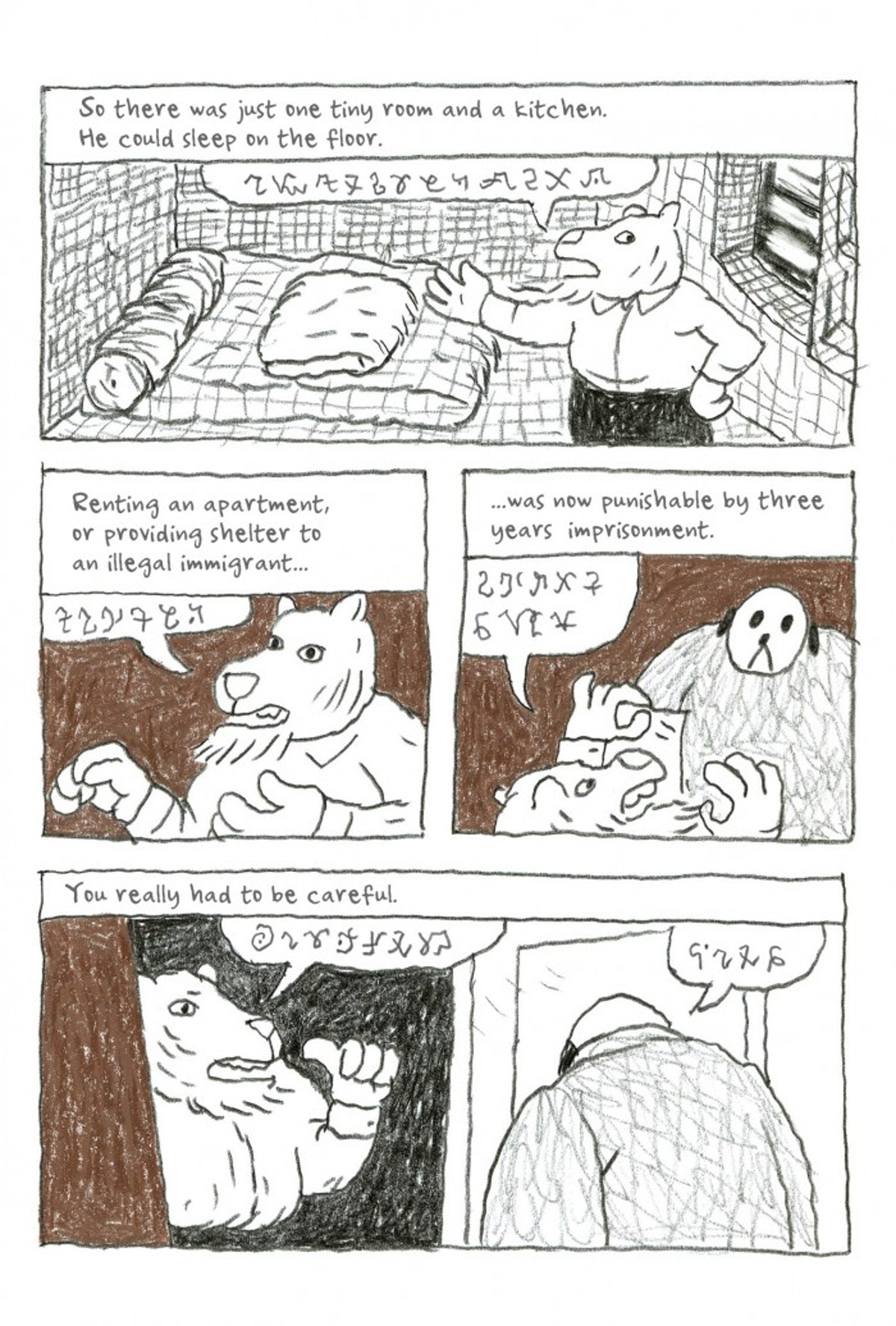

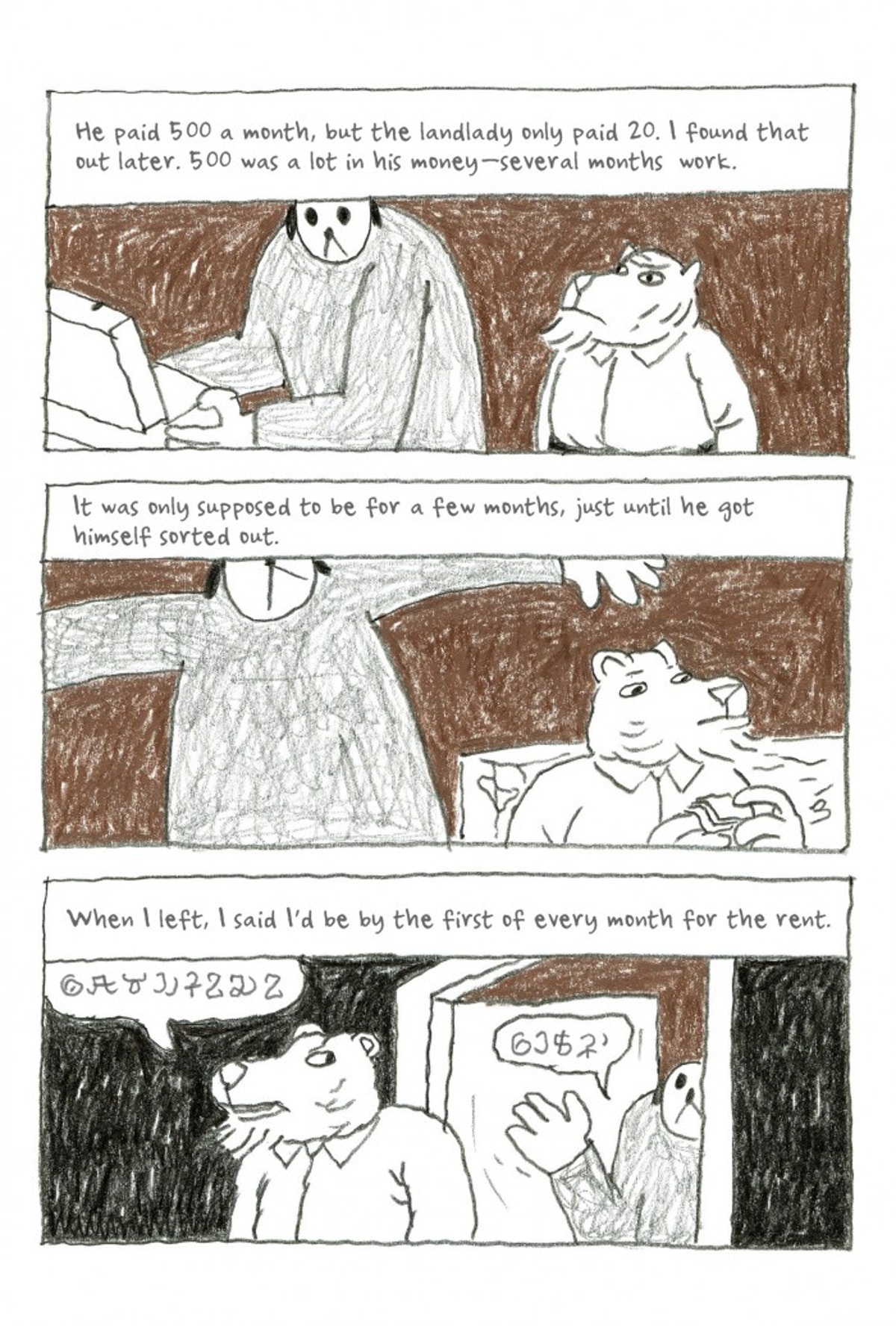

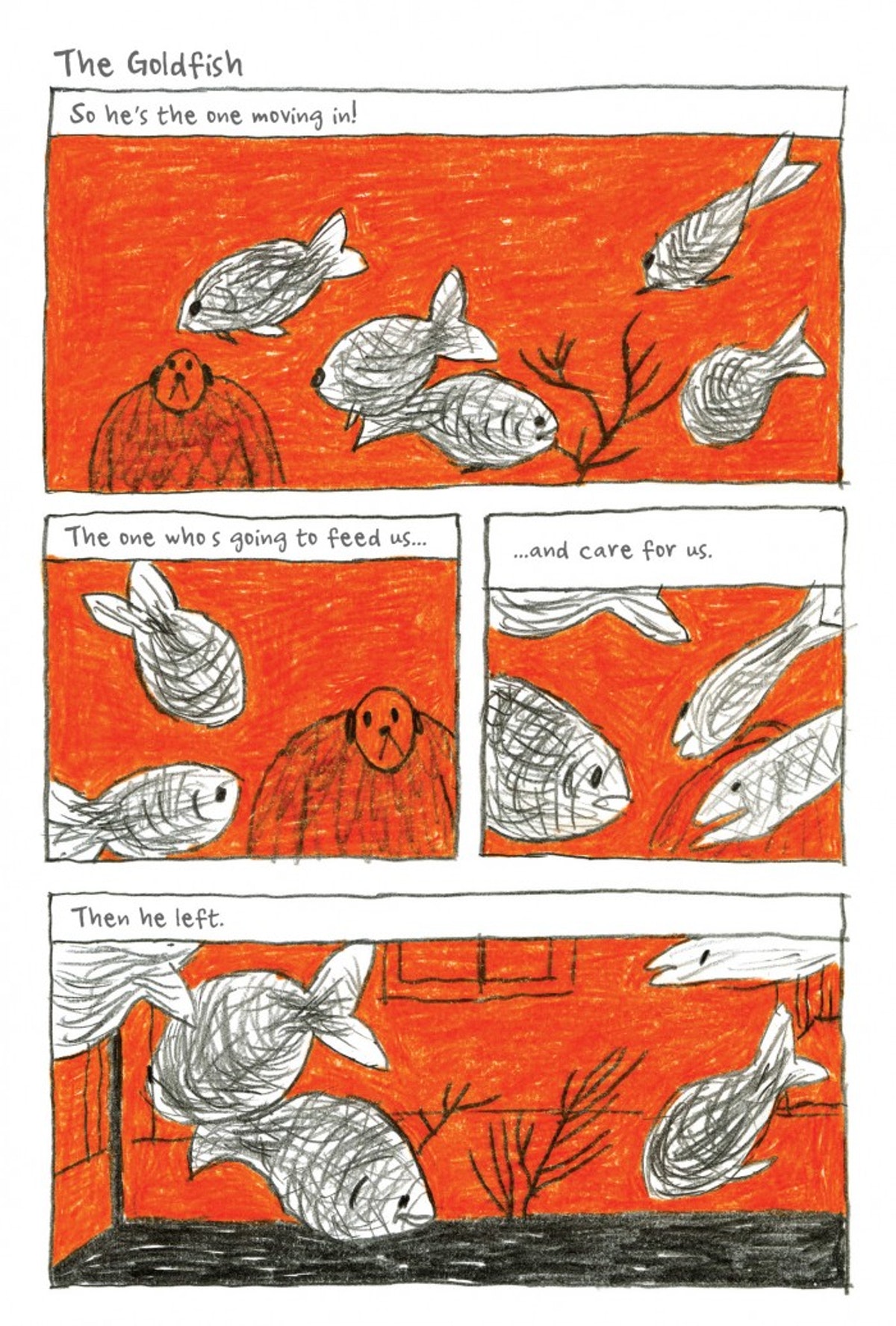

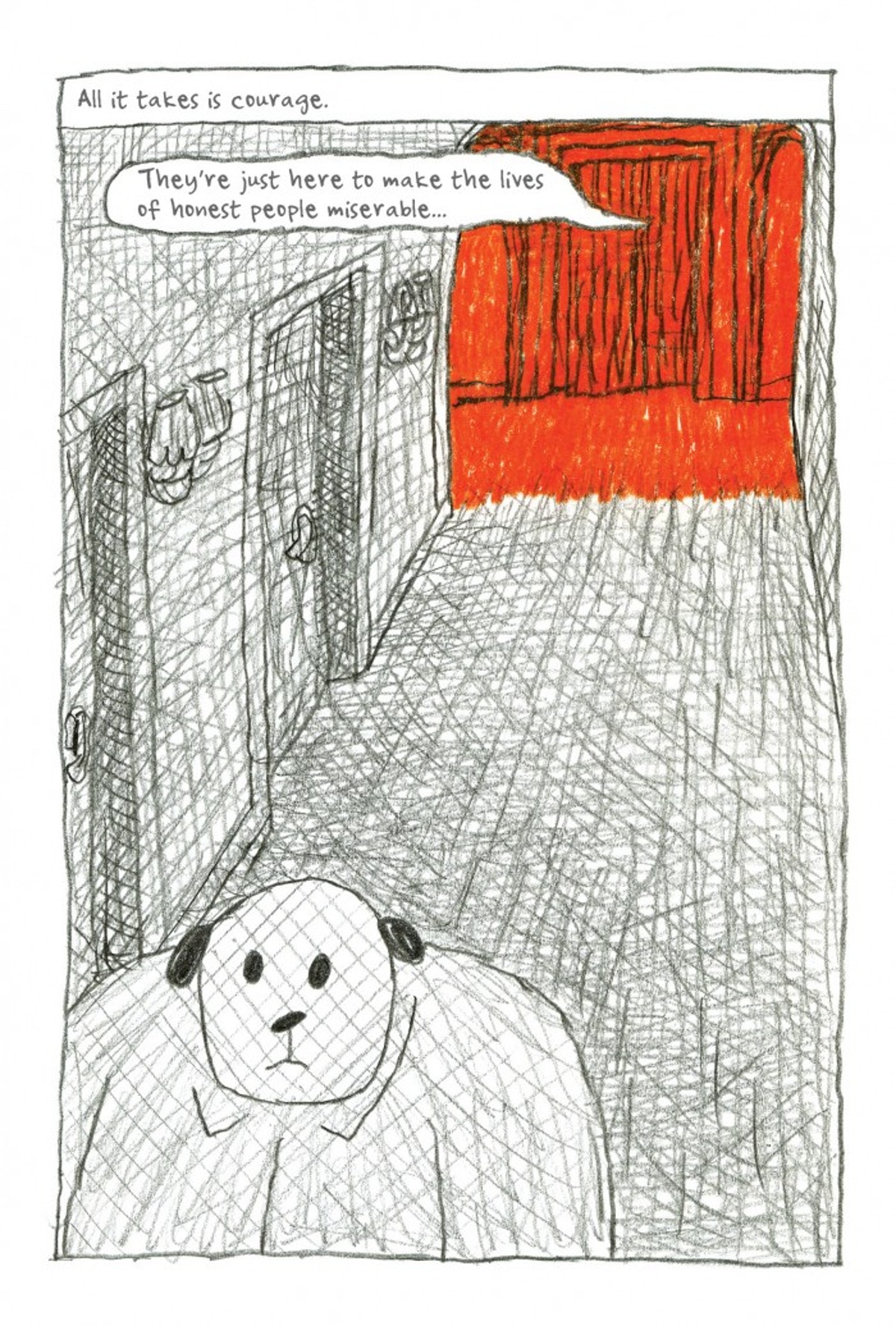

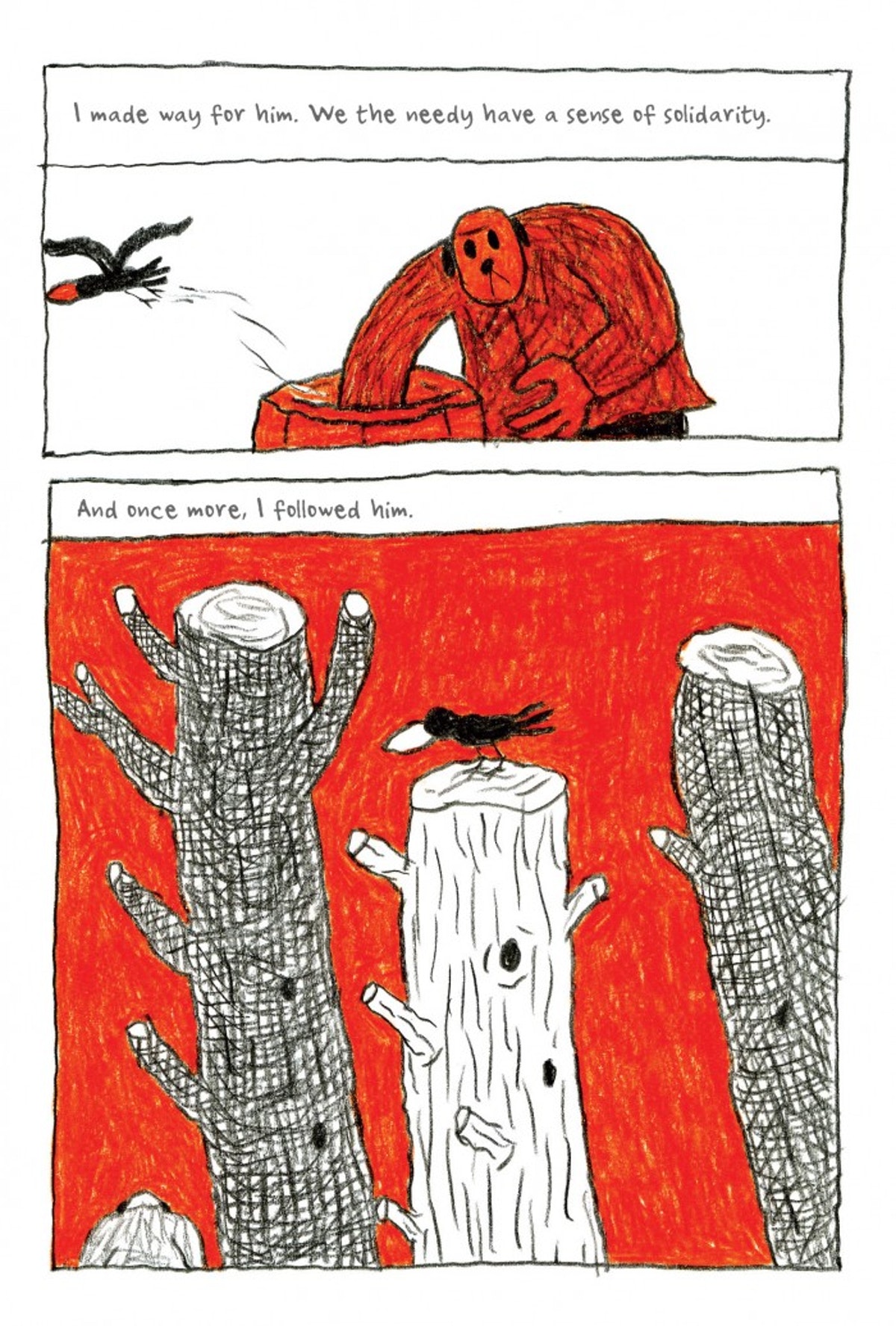

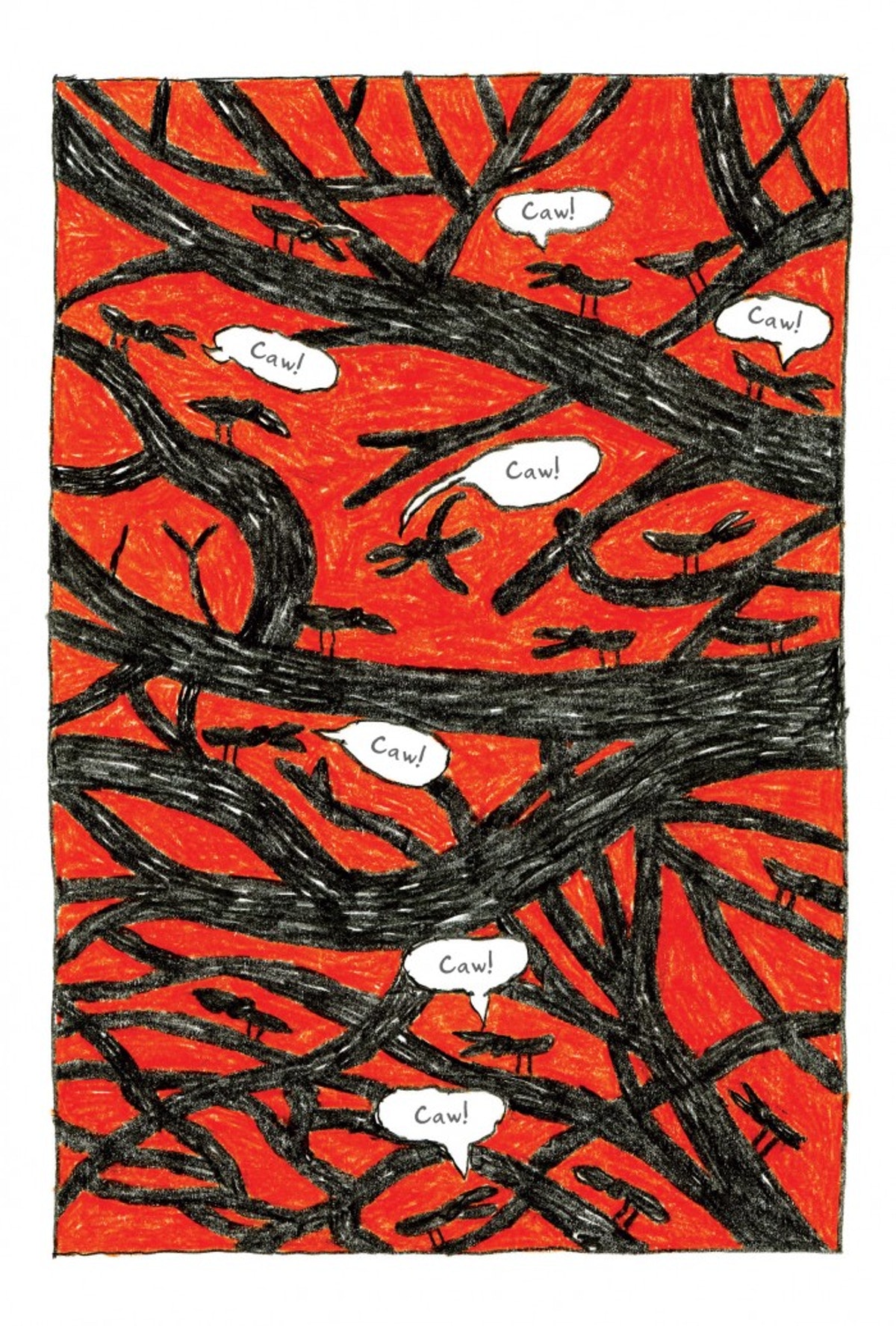

The word étrange is usually an adjective in French. Most commonly rendered as “strange,” it is also the traditional translation for the German unheimlich—literally, “unhomed”—for which we in English would say “uncanny.” When a noun, étrange generally refers to the state or quality of strangeness, and not an object, much less a person. Literally unhomed, his native tongue depicted as unearthly symbology, Ruillier’s protagonist meets with bewildering mishaps in this alienating metropolis, recalling literatures of the strange from Kafka to Kadaré to Ferenc Karinthy’s Metropole. As a figure, he inspires fear. Physically much larger than most other characters, he could be said to loom. Yet his face is constantly forlorn: an expression of confusion, sadness, and dismay.

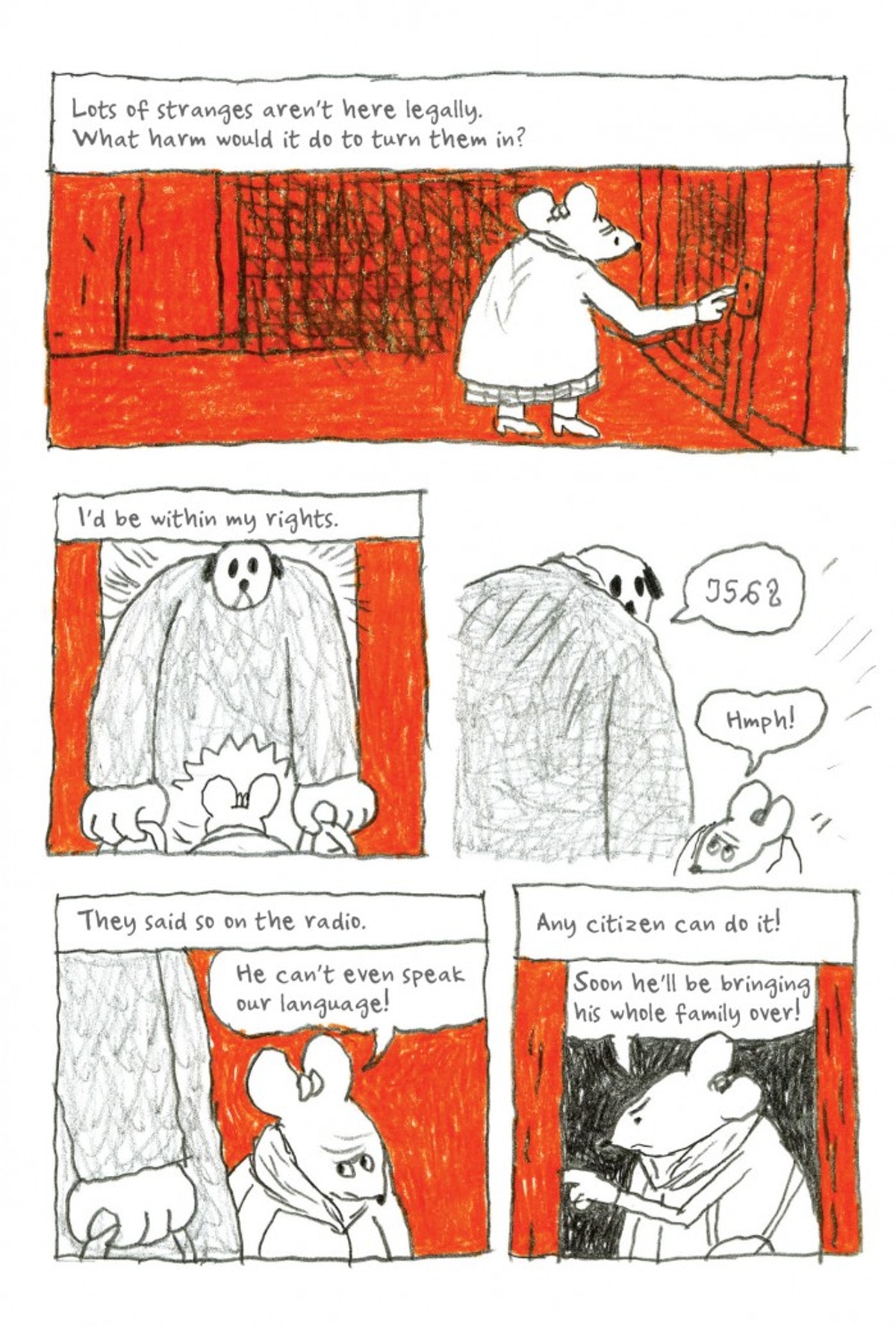

The words étrange and étranger are far from interchangeable, but given the context of Ruillier’s tale, any French reader would inevitably hear in the former the deliberate truncation of the latter. The French word for “foreigner,” étranger can also mean “outsider” or “stranger.” What English word could inhabit this nexus? I toyed with “outland” which, adjectivized with an –ish or an –er, could mean alternately strange or foreign. Like étrange, “outland” was less common as a noun, but in the end it seemed to err on the side of whimsy and geography at the expense of, well, estrangement. If calling someone a “strange” sounds ungainly, it is meant to: to draw attention to the exclusionary root in our relations with the foreign. In English and French alike, the plural, applied indiscriminately to swaths of population, sounds even odder, more misplaced, the tactic of those who would rather not know.

Few English readers, upon picking up Albert Camus’s most famous novel, will remember that French readers cannot help hearing the trinity of meanings in L’Étranger (though there is no shortage of articles to remind us). From these meanings the English title highlights one—the existential, almost abstracted condition of being a stranger—the sort of selection that usually gets translation blamed for loss. Rather, consider this: the reading of Camus that informed this choice has given the novel a durable and generative identity in a new national context, one that in turn expanded the suggestive possibilities of a word we believed our own. In the game of cultural allusion that is language, to say “stranger” in English now is to hear, however faintly, an echo of alienation a la Camus. Translation enables such negotiations, the process by which meanings, unhomed, migrate into new words: smuggled, struggling, mistrusted, and finally welcomed. Over time, the odd and frightening become familiar, and the familiar finds itself, by way of becoming odder and unafraid, enriched.

L’etrange © 2016 by L’Agrume. By arrangement with the publisher. Translation © 2016 by Edward Gauvin. Lettering by Irvin Carsten. All rights reserved.