A dead man’s greatest virtue is honesty.

—Machado de Assis, The Posthumous Memoirs of Brás Cubas

I found out I was dead when I started to write a book. It wasn’t this book yet.

I was living with my wife in an apartment two floors above a restaurant. The kitchen staff would get together on the restaurant’s back patio in the courtyard under that internal area where the buildings of the block form a polyhedron of public intimacy. There they would eat, smoke, talk on the phone, and gab. Their conversations traveled through the walls of my home. It was like living in Strindberg’s Inferno and hearing the voices that followed him through cheap hotels in Paris at the twilight of the nineteenth century. Except this was Rio de Janeiro, and unlike the Swedish writer, I wasn’t crazy.

Or at least that’s what I wanted to believe. When the loud conversations woke me up every morning and kept me from working during the day or screwing at night, I’d call the restaurant to complain about the noise. When my complaints were ignored, which was most of the time, I’d scream from the window: “Shut the fuck up, you sons of bitches!”

One night, after a brief exchange of curse words, I dumped the first thing I could find out the window: a garbage bag full of correspondence. In exchange someone threw a raw egg at my window. My wife started to cry. As the egg ran down the glass, they collected the garbage and went to the nearest police station.

The police cited me for the crimes of Threatening Behavior, Throwing Objects, and Public Endangerment under Incident Registry No. 014–03595/2011.

***

Three days later, a phone call woke me up at eleven in the morning. It was the last Saturday in April 2011.

“Hello.”

“Who’s speaking?”

“Who do you want to talk to?”

“Is this Mr. João Paulo?”

“Yes.”

“João Paulo Vieira Machado de Cue . . .” He hesitates.

“Cuenca.”

“Yes, that’s it. Son of Maria Teresa Vieira Machado and Juan José Cuenca?”

“Who’s calling?”

“I’m Inspector Gomes from the Fifth Police Precinct. We pulled your file here after the complaint about the restaurant incident.”

“Yes?”

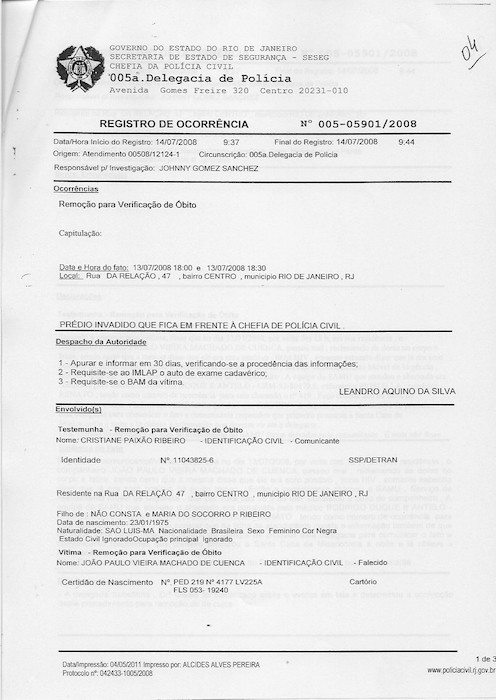

“It’s that we have another incident report here dated July 14, 2008, with your name on it.”

“Incident report?”

“Do you know what it’s about?”

“In 2008?”

“Right.”

“I have no idea.”

“This report documents your death.”

“What?”

“The registry of your death. It says here that you’re dead. Do you know a Cristiane Paixão Ribeiro?”

“Cristiane? No.”

“I think you’d better come down to the station to clear this up.”

“Now?”

***

On my way to the police station downtown, I looked out the taxi window at the beach.

Seen from the ocean, the car was a small metallic dot reflecting the sun as it advanced in front of the coil of buildings that lined the beachfront avenues. In the background the gigantic Tijuca Massif dominated the landscape in tones of green over rock.

The natural wall that divides Rio de Janeiro includes the hunchbacked ridge of the Corcovado Mountain, the Dois Irmãos, and the Pedra da Gávea, natural dividers between the South Zone, the North Zone, and the Barra da Tijuca. From atop the mountains, the sinuous panorama of the favelas spills down into a toothpick holder of buildings divided by the geometrical grid of asphalt avenues leading to the beach and the blue water. Perched on the topographical seesaw that mixes tile with the Atlantic rainforest, the poor watch the rich from above.

As much as they seem to be part of different universes, the favela dwellers have strong connections with their neighbors who occupy apartments of one thousand square meters behind mirrored facades reflecting the Atlantic. Many of the slum dwellers work in the homes of the white people who live on the asphalt—in the kitchen, as doormen, nannies, or chauffeurs—and sometimes they make deliveries of food, medicine, and cocaine. In turn, the bosses of the drug trade on the hillsides surrounding the South Zone and the power brokers of the luxury buildings on Avenues Delfim Moreira and Vieira Souto have even stronger ties.

The money trail involves high-ranking politicians, financiers, police officials, military, legislators, construction bosses, and neo-Pentecostal pastors who launder money for drug and arms traffickers. If at the retail point there are disposable black kids armed with guns on the dimly lit hillside arteries, on the other side there are prohibition lobbyists and drug wholesalers with Jacuzzis and paintings by Romero Britto and Beatriz Milhazes in their living rooms that look out onto the Atlantic Ocean.

Many of the residents of those marble buildings have no need to call the drug lords on the Morro do Vidigal or Rocinha when they want drugs. All they have to do is pick up the intercom to the penthouse and skip the intermediaries. It would be a discourtesy to even think about it.

After all, it was just one more weekend on the beach and the complacent citizens of Rio de Janeiro walked, ran, rode bikes, played variations of soccer on the sand—footvolley, goal to goal, altinho, and bobinho. They were drinking coconut water at the kiosks along Ipanema Beach, exercising on metal bars, tanning their well-nourished bodies while navigating the sidewalk. The women ignored them as they strolled in spandex two sizes too small, facing the emptiness with hurried steps.

It was on against this brilliant canvas that my parents met for the first time four decades ago. A man recently arrived from Argentina—he came in the mid-seventies seeking a sabbatical life and a suntan—and a girl from a formerly well-to-do family who worked in a real estate agency. They went to the same section of beach. I was born two years after that encounter, and unfortunately the luminous side of that young couple got lost in the genetics. If my father is optimistic and athletic and my mother is keen on affection, none of that carried over: from him I inherited the penchant for excess and unpaid work, and from her an irritable, anxious nature.

With the exception of a few brief episodes, I always rejected the exhibitionism of the beach. I rarely went, even though I lived only three blocks away.

“You don’t take advantage of it! It would be so healthy for you,” my wife often insisted.

A kid with a limited physique and a talent for being sickly. I perhaps rejected the beach because I liked to live outside my body. Or ignore it altogether and pretend that I was someone else. I was thinking about this as the city unfolded before me from Copacabana Beach to the Botafogo boardwalk. Afterward came the gardens of the Aterro do Flamengo, Glória, and then the center of the city announcing itself at the end of Praça Paris—all of this was once a big swath of sea later buried in tons of rock extracted from the Morro do Castelo. The hill on which the city was founded, the Morro was completely demolished along with its 470 buildings, churches, houses, and plots of land at the beginning of the 1920s. Its original dimensions were sixty-three meters high and eighteen thousand square meters wide.

My father liked to remind me: “Less than a century ago this wide avenue, the French gardens, and even this taxi were underwater. The water reached all the way to the Outeiro da Glória.”

In the air-conditioned car, the sun outside reminded me of the installations of the Colombian artist Oscar Muñoz, whose work I’d seen recently in a newly opened museum.

It was a video that showed a man’s hand drawing a face on a concrete floor. The drawing was made with a paintbrush dipped in water. Its features disappeared as the water evaporated—it seemed to be a hot day like today, perhaps with the same mesmerizing midday sun. The man’s hand retraced the recently erased features, but he had to quickly go back to touch up other parts of the face that were disappearing. The video followed this work of recomposition for an hour. As much as the man tried to maintain the original personality of the portrait, the shapes of the face changed while they were being reconstructed in that strange and unique race against time. If the man spent more than ten seconds without retouching the portrait it would disappear completely.

***

Rio de Janeiro’s Fifth Precinct Police Station is in a low building annexed to the Civil Police Headquarters on Avenida Gomes Freire in the Lapa district. The complex guards the architectonic pentimento of the city center: window boxes, postmodern skyscrapers, art deco gates, buildings inspired by French architecture, and town houses in the Portuguese tradition—many falling to pieces. Like the one next to the station with just the facade left standing, its windows opening a space to the sky and a bare patch of land.

After identifying myself to a police officer, I was led through hallways lined with boxes of files to the detective inspector’s office. Each one of those files, forming an enclosure around tables and chairs and leaving few walls visible, contained narratives whose common theme was misunderstanding between the human beings of my city. Stories transmitted orally by its inhabitants and registered by clerks, which made the place a lost crossroads between a library, registry, and morgue.

“So you’re Cuenca, huh?”

Inspector Gomes is bald, about fifty, and wears a shoulder holster. Without getting up from his chair, he stretches out his hand in a loose greeting. The atavistic fear that I feel in the presence of professors, priests, and policemen is a personality trait that has accompanied me since childhood—I’ve never felt at ease in front of an agent of the law. It would not be the first time.

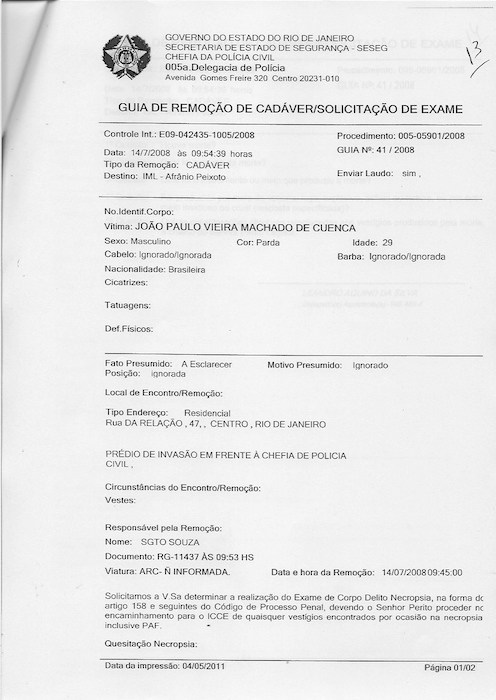

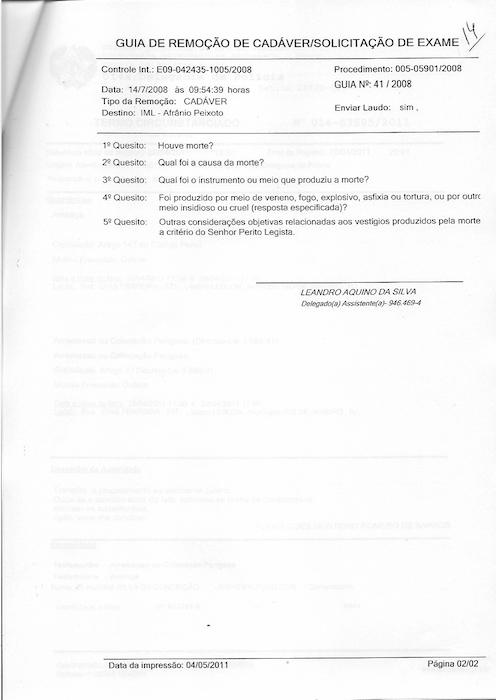

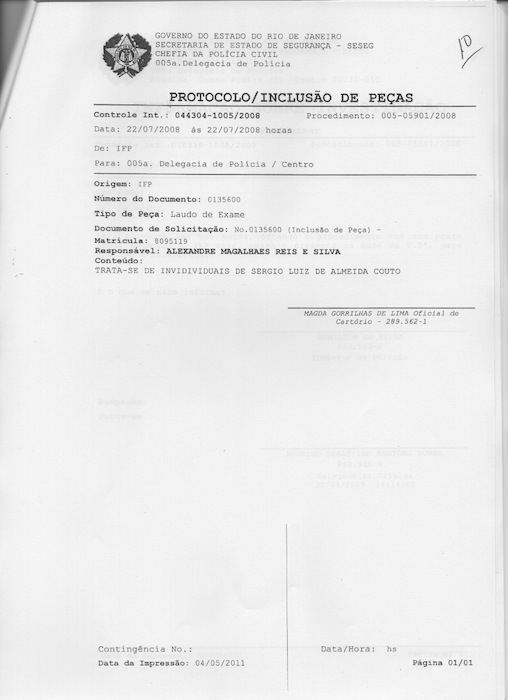

The inspector seems to notice my discomfort and smiles with the air of someone who is keeper of the keys to the jail cell. Then he orders me to sit down and tosses on the desk the Registry of Incident 005–0591/2008, the Protocol for Removal of Corpse 042435–1005/2008, and Death Certificate 04331/08—all certifying that João Paulo Vieira Machado de Cuenca, son of Maria Teresa Vieira Machado and Juan José Cuenca, whose birth certificate number is PED2194177LV255A, is dead.

With a look that was somewhere between threatening and curious, the police officer studied my reaction as I read the incident report. Then he asked questions that you never imagine you’ll hear: “Where were you on July 14, 2008?”

I looked at the clock on the wall. It was 12:05—it was stopped. I don’t know why, but it seemed to be showing five minutes after midnight and not five minutes after noon.

I was in Rome. The date of the incident that registered my death by lobar pneumonia with formation of microabscesses, encephalitis with the presence of structures suggestive of oocytes of toxoplasma gondii, edema, and areas of intracranial hemorrhaging in an abandoned building on Rua da Relação, 47, between Rua dos Inválidos and Avenida Gomes Freire, just a few meters away from that police station, was the same as the date of the launch of the Italian translation of my second novel, Mastroianni’s Day, at the Libreria del Cinema, a small bookstore in Trastevere.

In February 2008, after a divorce, I left Rio with no fixed date of return, following a pattern that had become routine of accepting invitations for book launches or lectures abroad and adding on trips that kept getting longer and more pointless. The disingenuous belief in the departure—the same original sin of Europe, of Dom Sebastião, of my ancestors, of generations of immigrants and displaced people falling like domino pieces far from home—masked a certain moroseness and vague desires to disappear. I still didn’t understand that my personality would not be constructed by an accumulation of experiences, but rather eroded by them.

After a writer’s conference in Portugal, a stay of a few weeks in Spain, and a month in France, I arrived in Rome after a long train trip. I was feeling the vague, solitary happiness of travelers. It was summer, the day sparkled all over Europe, and I was holding on to the memory of a few naked women in the small studio behind the green door of Rue du Temple, 94, in Paris, and I was in love with one of them. I was returning to Rome to promote a translation and I was the perfect example of the young starving Latin American writer dazzled by the European experience.

The book launch at sunset in Trastevere, the dawn that I spent on the rear seat of the scooter driven by the Italian with full breasts and hooked nose with whom I had shared a pipe of hash and a few kisses under the galleries of the Pantheon, maybe that had been some kind of apex, the top of the mountain from which today I observe the valleys and gesture at the point of inflection.

***

“Where were you the night of July 14, 2008?”

“2008?”

“Yes.”

“In July? In July 2008 I was in Europe. I stayed until the end of the month, or into August.”

“Vacation?”

“Work.”

“Work?”

“I’m a writer.”

“What do you write about?”

“I was invited to some literary festivals. I launched a translation of a book of mine in Italy.”

“Are you a famous writer?”

“No.”

“Sorry, but I’ve never heard of you. And you have a strange name.”

“Right.”

“What do you write?”

“Fiction.”

“Books?”

“Yes.”

“Science fiction?”

“No. I mean, it could be.”

“What’s in your books?”

“I don’t know, it’s complicated.”

“What do you mean, complicated?”

“It’s that if you ask any writer . . .”

“Do you think I’m ignorant?”

“Of course not.”

“I’m a lawyer. I read a lot. I’ve read a lot. There was a time I read all of the books by Rubem Fonseca. You know him?”

“Do I know Rubem Fonseca?”

“Yes.”

“I like Rubem Fonseca very much. He might be the author who had the most—”

“There’s a sentence by him that I love. I always use it.”

“What is it?”

“There’s nothing that a woman can’t make worse.”

“That’s a good one.”

“It is, isn’t it?”

“Yeah.”

“You’ve got this woman here, for example.”

“Who?”

“That one. It’s on the registry. She’s the one who identified the body with your name, address, and document number. That Cristiane.”

“She’s alive?”

“She was summoned to clarify the story. But the address doesn’t match up.”

“Do you have any idea why that woman would have done such a thing?”

“Hey, my friend. There are stories I could tell . . .”

“I bet.”

“She could be committing insurance fraud in your name.”

“In my name?”

“Yes, and you could be an accomplice.”

“Me?”

“I’m just kidding. But did you have any insurance in your name in 2008?”

“I’ve never had life insurance.”

“Never?”

“Not that I know of.”

“Have you had any credit problems lately?”

“Yes, but they were all my fault.”

“No personal loans in your name?”

“No.”

“Then that guy just used your name to die.”

“He must have been running away from someone.”

“Yeah, but why did his wife identify him with your name and not his real one?”

“He was already dead, a guy like him didn’t have a pension coming.”

A young woman appears with a folder and leaves it on the desk. She has blonde hair and wears jeans. Her holster is empty. Inspector Gomes asks her for coffee and offers me some. I accept. The policewoman responds to my attempt at a smile with a resigned nod of her head and disappears down an aisle between the tables to the end of the hall. We both follow the pendular movement of her buttocks, our only moment of complicity that afternoon. The inspector returns to business, as if he just remembered something.

“People usually steal someone’s identity to run away from something, to try another life. It’s very common for a bum to steal the identity of a dead man to live with his name. But that’s . . .”

“That’s what?”

“I don’t know. This is strange as hell.”

“How did he get hold of my birth certificate?”

“You tell me. Have you lost it?”

“Never.”

“But you’re in luck. Didn’t you notice in the paperwork that they identified his body after a week?”

“They identified it?”

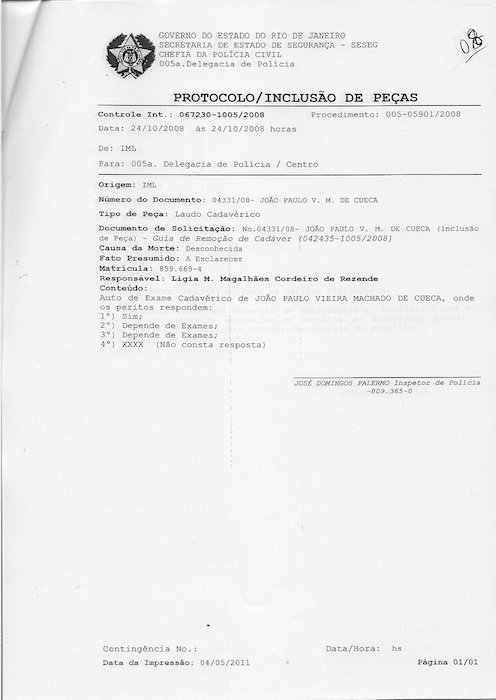

He showed me this piece of paper:

“That Sérgio there. They made the dead guy play the piano and that’s what saved you.”

“Piano?”

“Fingerprints. That’s the only reason there’s not a death certificate in your name. You’d have been fucked.”

“Why?”

“It’s a bitch to try to prove you’re alive. You think you just have to be breathing?”

“Who would have thought.”

“Thought what?”

“That it was easy.”

“Right.”

“So who was this guy?”

“Look, I don’t know. But he wasn’t a good guy.”

“Can you bring up his file?”

“Yeah, but the system’s down.”

“Do you know when it will come back up?”

“If only I knew . . . Anyway, you can relax. I’ll make a note here that you were out of the country and didn’t know anything about this incident, and that you didn’t know that Miss Cristiane either.”

“And now what?

“I have your contact information. If we need you, I know how to find you. Are you planning on traveling abroad in the next few months?”

“Yes, why?”

“No, nothing.”

“Can I keep a copy of those papers?”

“What do you want with them?”

“I don’t know. I’d like to read them carefully.”

“It’s a story a writer can use.”

“Right.”

“Are you going to write a book about it?”

“No.”

I left the police station. I never did get that coffee.

From Descobri que estava morto. © 2016 by J. P. Cuenca. By arrangement with the author. Translation © 2019 by Elizabeth Lowe. All rights reserved.